Tuesday, 3 December 2013

Is this plagiarism?

So I noticed some similarities between my earlier blog on today's PISA results and Wednesday morning's Times leader column.

Below I've quoted the leader column followed by the similar line from my blog in italics.

Plagiarism or sloppiness?

"Economies such as Brazil, Indonesia, Mexico and Turkey are starting to educate their populations better too, especially in reading."

"The charts below show the countries that have consistently improved in reading...what stands out is the number of "emerging economies" in this group like Brazil; Indonesia; Mexico and Turkey."

"The same is true of many of the former Warsaw Pact countries such as Estonia, Poland, Russia and Hungary, all of which are improving quickly."

"We can also see big improvements in many of the former USSR/Warsaw Pact countries like Estonia, Poland, Russia and Hungary."

"The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) points out that nations in the Far East do well because they have a cultural fixation with hard work rather than any innate ability."

"The OECD argue that the single biggest reason why the Far East does so well is that they do not have the fixation with innate ability that many Western countries have."

"Many of the most improved nations, such as Estonia, Mexico and Israel, have recently been making their entry criteria to the teaching profession tougher."

"Many of the most improved countries like Estonia, Mexico and Israel have been toughening entry criteria to the profession"

"The countries that do well have, without exception, what the OECD calls “system stability”.

"Most [successful countries] have "system stability"

That last one's a bit of a giveaway - I use the phrase "system stability" but it doesn't appear anywhere in the OECD report...

10 Things You Should Know About PISA

`

1. PISA isn't precise but isn't useless either. No methodology designed to compare countries with completely different cultures and education systems will ever be perfect. The OECD acknowledge that their rankings aren't exact and it makes more sense to look at buckets of countries who have similar scores:

It may be that they're underplaying the statistical issues with the tests (see Professor David Spiegelhalter's concerns here). But that doesn't mean that PISA is worthless. In fact it's far more reliable (along with the other global tests - TIMSS and PIRLS) than any other method of comparison. While we shouldn't rely on the exact rankings we can look at broad trends - especially over time.

2. PISA tests something quite specific. The questions PISA uses are applied - i.e. are focused on using literacy and numeracy in "everyday" situations. Some education systems focus their curriculum more on this type of learning than others. By contrast TIMSS tests whether pupils have mastered specific knowledge and skills which, again, some systems focus on more than others. The UK and US do much better in TIMSS than PISA - and always have.

So with those caveats...

3. The UK is very very average. In Maths and Reading there's no statistically significant difference between the UK and the OECD average. Even on each individual question type (subscales) in Maths the UK is bang on average. Only in Science is the UK slightly above average - as it was last time. There is also no real change from the previous round of PISA. The UK's science score is exactly the same as last time; while Maths and Reading have seen a fractional but not significant improvement. As the graph below shows the UK is one of fairly large group of countries that have seen no meaningful change over the past ten years. All those policies; all those rows and - at least on what PISA measures - no change.

4. The Far East is dominant. Far Eastern countries have always done well in PISA but they are moving away from everyone else. The top seven jurisdictions in Maths are all Far Eastern (though four of the seven are cities or city-states). Shanghai's 15 year olds are now a full three years ahead of the OECD average - and thus the UK - in Maths (40 points translates roughly into one year of learning). Also look, in the table below, at the number of "top performers" in Shanghai compared to the OECD average:

It's worth noting that there are some question marks about Shanghai's performance. For instance they exclude the children of migrant workers. And of course Shanghai is not China. If you plucked London out of the UK it would almost certainly do better than the country average.

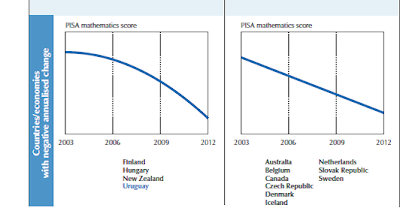

5. Scandinavia is in decline. One of the big stories from this PISA dataset is Finland's significant drop - especially in Maths. They've actually been declining over the past few iterations but the drop this time is much bigger. In fact they're one of only four countries where Maths scores are falling at an accelerating pace (see chart below on the left). But something broader is happening in Scandinavia. If you look at the chart on the right you can see Denmark, Sweden and Iceland have been falling steadily over the past ten years too. Norway has remained static over the same period. Given these countries have fairly different policy environments there may be demographic factors at play here - for instance increasing immigration could be making these countries less socially homogenous.

6. The emerging economies are on the rise. The charts below show the countries that have consistently improved in reading since 2000. While there's a mix of different countries; what stands out is the number of "emerging economies" in this group like Brazil; Indonesia; Mexico and Turkey. These countries are starting from a low base and still do considerably worse than the UK and other developed nations but their rapid improvement is encouraging from the perspective of global prosperity. Often the improvement in these countries is a result of getting more children into school and keeping them their longer. Between 2000 and 2011 the number of children not in school, globally, fell by almost half. We can also see big improvements in many of the former USSR/Warsaw Pact countries like Estonia, Poland, Russia and Hungary. The former two are now among the best performers in Europe.

7. National scores hide huge regional variations. Some countries run the tests in such a way as to allow sub-regions to be given separate scores. The differences are often startling. For instance the Trento region in the north of Italy would be in the top ten globally for Maths if it was a country but pupils in Calabria in the south are around two and half years behind. Likewise in Australia pupils in the Capital Territory (i.e. Canberra) are almost two years ahead of those in the Northern Territory (where many indigenous Australians live). And Flemish Belgium does miles better than French Belgium. In the next PISA we'll be able to see England by region and we can expect to see London and the South-East outperforming other areas. We can already see Wales significantly underperforming the rest of the United Kingdom - the gap's got fractionally larger since last time.

8. There are some policies that many of the "rising" countries seem to share. One of the trickiest things about PISA is making causal links between specific policies and changes in countries' scores. It's very hard to not just cherry-pick examples that support one's existing views. There do seem to be, though, some strong themes around the most successful and most improved countries. One is selection - Germany and Poland are both reducing selection in their systems and have seen improvements and a reduction in the impact of socio-economic status on performance. Singapore is really the only high-performing country to have any selection in their system. A focus on the status of teaching does also seem to be important. This has always been true in the Far East but many of the most improved countries like Estonia, Mexico and Israel have been toughening entry criteria to the profession; raising teacher pay and improving access to professional development. Most successful countries also seem to give a reasonable amount of autonomy to schools. And most have "system stability" - i.e. they have planned reforms backed by much of the system taking place over an extended period of time; rather than constant, uncoordinated, changes.

9. High expectations are absolutely key. The OECD argue that the single biggest reason why the Far East does so well is that they do not have the fixation with innate ability that many Western countries have (yes I'm looking at you Boris). As they put it:

"The PISA 2012 assessment dispels the widespread notion that mathematics achievement is mainly

a product of innate ability rather than hard work. On average across all countries, 32% of 15-year-olds do not reach the baseline Level 2 on the PISA mathematics scale (24% across OECD countries), meaning that those students can perform –at best – routine mathematical procedures following direct instructions. But in Japan and Korea, fewer than 10% of students – and in Shanghai-China, fewer than 4% of students – do not reach this level of proficiency. In these education systems, high expectations for all students are not a mantra but a reality; students who start to fall behind are identified quickly, their problems are promptly and accurately diagnosed, and the appropriate course of action for improvement is quickly taken."

10. There's loads more interesting stuff. The above points are all taken from Volume 1 of the PISA report. There are another five volumes that will need to be trawled for further insights. Volume 2 is particularly important because it looks at the impact of socio-economic status (SES) on performance. Again SES seems to explain an average amount of the UK's variation but in the most successful countries it plays much less of a role.

Here's the link to the full report: bit.ly/PISA2012

1. PISA isn't precise but isn't useless either. No methodology designed to compare countries with completely different cultures and education systems will ever be perfect. The OECD acknowledge that their rankings aren't exact and it makes more sense to look at buckets of countries who have similar scores:

It may be that they're underplaying the statistical issues with the tests (see Professor David Spiegelhalter's concerns here). But that doesn't mean that PISA is worthless. In fact it's far more reliable (along with the other global tests - TIMSS and PIRLS) than any other method of comparison. While we shouldn't rely on the exact rankings we can look at broad trends - especially over time.

2. PISA tests something quite specific. The questions PISA uses are applied - i.e. are focused on using literacy and numeracy in "everyday" situations. Some education systems focus their curriculum more on this type of learning than others. By contrast TIMSS tests whether pupils have mastered specific knowledge and skills which, again, some systems focus on more than others. The UK and US do much better in TIMSS than PISA - and always have.

So with those caveats...

3. The UK is very very average. In Maths and Reading there's no statistically significant difference between the UK and the OECD average. Even on each individual question type (subscales) in Maths the UK is bang on average. Only in Science is the UK slightly above average - as it was last time. There is also no real change from the previous round of PISA. The UK's science score is exactly the same as last time; while Maths and Reading have seen a fractional but not significant improvement. As the graph below shows the UK is one of fairly large group of countries that have seen no meaningful change over the past ten years. All those policies; all those rows and - at least on what PISA measures - no change.

4. The Far East is dominant. Far Eastern countries have always done well in PISA but they are moving away from everyone else. The top seven jurisdictions in Maths are all Far Eastern (though four of the seven are cities or city-states). Shanghai's 15 year olds are now a full three years ahead of the OECD average - and thus the UK - in Maths (40 points translates roughly into one year of learning). Also look, in the table below, at the number of "top performers" in Shanghai compared to the OECD average:

It's worth noting that there are some question marks about Shanghai's performance. For instance they exclude the children of migrant workers. And of course Shanghai is not China. If you plucked London out of the UK it would almost certainly do better than the country average.

5. Scandinavia is in decline. One of the big stories from this PISA dataset is Finland's significant drop - especially in Maths. They've actually been declining over the past few iterations but the drop this time is much bigger. In fact they're one of only four countries where Maths scores are falling at an accelerating pace (see chart below on the left). But something broader is happening in Scandinavia. If you look at the chart on the right you can see Denmark, Sweden and Iceland have been falling steadily over the past ten years too. Norway has remained static over the same period. Given these countries have fairly different policy environments there may be demographic factors at play here - for instance increasing immigration could be making these countries less socially homogenous.

6. The emerging economies are on the rise. The charts below show the countries that have consistently improved in reading since 2000. While there's a mix of different countries; what stands out is the number of "emerging economies" in this group like Brazil; Indonesia; Mexico and Turkey. These countries are starting from a low base and still do considerably worse than the UK and other developed nations but their rapid improvement is encouraging from the perspective of global prosperity. Often the improvement in these countries is a result of getting more children into school and keeping them their longer. Between 2000 and 2011 the number of children not in school, globally, fell by almost half. We can also see big improvements in many of the former USSR/Warsaw Pact countries like Estonia, Poland, Russia and Hungary. The former two are now among the best performers in Europe.

7. National scores hide huge regional variations. Some countries run the tests in such a way as to allow sub-regions to be given separate scores. The differences are often startling. For instance the Trento region in the north of Italy would be in the top ten globally for Maths if it was a country but pupils in Calabria in the south are around two and half years behind. Likewise in Australia pupils in the Capital Territory (i.e. Canberra) are almost two years ahead of those in the Northern Territory (where many indigenous Australians live). And Flemish Belgium does miles better than French Belgium. In the next PISA we'll be able to see England by region and we can expect to see London and the South-East outperforming other areas. We can already see Wales significantly underperforming the rest of the United Kingdom - the gap's got fractionally larger since last time.

8. There are some policies that many of the "rising" countries seem to share. One of the trickiest things about PISA is making causal links between specific policies and changes in countries' scores. It's very hard to not just cherry-pick examples that support one's existing views. There do seem to be, though, some strong themes around the most successful and most improved countries. One is selection - Germany and Poland are both reducing selection in their systems and have seen improvements and a reduction in the impact of socio-economic status on performance. Singapore is really the only high-performing country to have any selection in their system. A focus on the status of teaching does also seem to be important. This has always been true in the Far East but many of the most improved countries like Estonia, Mexico and Israel have been toughening entry criteria to the profession; raising teacher pay and improving access to professional development. Most successful countries also seem to give a reasonable amount of autonomy to schools. And most have "system stability" - i.e. they have planned reforms backed by much of the system taking place over an extended period of time; rather than constant, uncoordinated, changes.

9. High expectations are absolutely key. The OECD argue that the single biggest reason why the Far East does so well is that they do not have the fixation with innate ability that many Western countries have (yes I'm looking at you Boris). As they put it:

"The PISA 2012 assessment dispels the widespread notion that mathematics achievement is mainly

a product of innate ability rather than hard work. On average across all countries, 32% of 15-year-olds do not reach the baseline Level 2 on the PISA mathematics scale (24% across OECD countries), meaning that those students can perform –at best – routine mathematical procedures following direct instructions. But in Japan and Korea, fewer than 10% of students – and in Shanghai-China, fewer than 4% of students – do not reach this level of proficiency. In these education systems, high expectations for all students are not a mantra but a reality; students who start to fall behind are identified quickly, their problems are promptly and accurately diagnosed, and the appropriate course of action for improvement is quickly taken."

10. There's loads more interesting stuff. The above points are all taken from Volume 1 of the PISA report. There are another five volumes that will need to be trawled for further insights. Volume 2 is particularly important because it looks at the impact of socio-economic status (SES) on performance. Again SES seems to explain an average amount of the UK's variation but in the most successful countries it plays much less of a role.

Here's the link to the full report: bit.ly/PISA2012

Sunday, 24 November 2013

What next for Ofsted?

Ofsted isn't going to be abolished (nor should it be)

A few weeks ago Old Andrew wrote a typically incisive, and popular, post explaining why he felt Ofsted are now beyond redemption and should be abolished.

That isn't going to happen. Ofsted is absolutely essential to the regulatory model the coalition Government have constructed. Failing academies and free schools can only be shut down on the basis of a poor inspection - there's no other legal mechanism (unless they mess up their finances or do something illegal). Likewise the Teaching School / National Leader of Education processes rely on Ofsted identifying outstanding schools.

And as Andrew notes in this post there's no indication that Labour would behave differently. If anything they envisage a bigger role - in recent weeks Tristram Hunt has argued for separate inspection of academy chains.

But even if the politicians were arguing in favour of abolition - and some way was found to deal with all the structural problems that would create - I'd be opposed. One of the OECD's clearest findings from PISA is that the worst type of education systems are those with high autonomy and low accountability (conversely the best are high autonomy and high accountability). While it may not feel like it to classroom teachers we have one of the highest autonomy systems in the world. Most secondary schools now have control of their own curriculum; nearly all funding in the system is passed directly to schools; teacher training is increasingly run through schools too.

So while I think there are lots of ways we can make our accountability system smarter I don't think we should be removing a key mechanism for holding schools to account. If we did then we'd be left with exam data as the only basis for accountability. Yet we know that schools can game test-based accountability by choosing easier options; focusing on certain pupils; or simply spending a lot of time cramming. While I've never been to a great school getting bad exam results; I have been to bad schools that get decent results. We have to have a way to check the quality of education on offer that goes beyond gameable data. There's a reason that most countries have some form of school inspection (and many of those that didn't have introduced inspectorates over the past decade).

That doesn't mean there isn't a problem

Although I think Ofsted needs to be an important component of our regulatory system I recognise the validity of many of the criticisms (and wrote about them here). This is not just the standard whinging you'd expect from any profession about its regulator.

There are two separate but related issues.

First a percentage of inspectors are not following the framework. They are insisting on seeing certain types of teaching in lesson inspections. It's unclear how large this percentage is but there are enough "rogue" inspectors to leave school leaders uncertain about how to prepare for inspections. That means many schools are doing things that are not required by the framework - and go against the spirit of that framework's intentions - because they don't know what "type" of inspector they are going to get.

Secondly lesson observations have limited validity - even if being done properly. Professor Rob Coe gives the technical details in these slides. But it's actually pretty obvious that in most cases it won't be possible to accurately tell how good a teacher is from a single 20 minute observation - even if it's done well. It's also hard not to let prejudices slip into judgements.

Katie Ashford explained here how teachers should approach an inspection of their lesson - and a good inspector like Mary Myatt will respond well to that. But it's understandable that many feel this is a risky strategy and end up teaching to what they think Ofsted wants to see rather than what's in the best interest of their class.

So what needs to change?

The first, fairly obvious thing, is to stop grading individual lessons. It's not clear at all what the benefit of doing this is given the lack of validity. It would be possible to build greater validity around observations but would require multiple observations by people rigorously trained in the same scoring system. And that's too expensive and complex for Ofsted to introduce.Scrapping individual lesson judgements would significantly reduce the problems Ofsted causes. Teachers would feel under less pressure to deliver a specific type of "outstanding" lesson; they wouldn't feel unfairly judged when their lesson gets a grade 3 or 4; and schools wouldn't feel so bound to using Ofsted grades in their own lesson inspections (and could move away from scored observations all together).

It wouldn't reduce the validity of the overall inspection as the lesson judgements aren't particularly valid anyway.

Instead inspections should focus more on systems. Essentially Ofsted should be looking at what the school is doing to ensure consistent good teaching. They should be inspecting the school's quality assurance not trying to do the quality assurance themselves in the space of two days (good inspectors will see this as their role already - but it's nowhere near explicit enough).

In their observations of lessons they should be checking the leadership know their teachers and understand how best to support their future development. They should be checking that they have thought about professional development and about performance management (which shouldn't have to involve performance-related pay). They should be seeing if the behaviour policy is being enforced; and if the school curriculum is actually being used. This blog does a good job of showing how that might work in practice.

I'm not sure there even needs to be an overall grade for teaching. After all if the leadership's good (because there's consistent practice across the school) and the attainment is good then the teaching will, almost by default, be good too. Likewise if the leadership is poor then the school isn't good even if there are pockets of excellent teaching (as there nearly always are in bad schools).

In addition to this simple, if bold, change Ofsted should make use of their new regional structure to announce a full reset so that everyone in the system - inspectors and schools - have a shared understanding of the purpose of inspection. This could involve, for example, retraining all inspectors alongside representatives from local schools; licensing inspectors through published exams; banning lead inspectors from acting as consultants and, as Rob Coe suggests, introducing transparent and independent processes for quality assuring inspections. This would need to be communicated via a major campaign from Ofsted, DfE, and, ideally, Head's associations.

Perhaps this wouldn't be enough to restore everyone's confidence in inspection but I'd much rather try to improve what we have than push the system into total reliance on test data.

Saturday, 9 November 2013

75 education people you should follow

One of the most frequent conversations I have is people asking me who they should follow on twitter. This is my attempt to answer. It is, of course, a highly subjective list based on people I enjoy following. But the people here represent a wide range of views / opinions. Follow this lot and you'll get a feel for the debate; as well as a good stream of useful links and some great blogs.

The list is ordered alphabetically in categories. The * indicates they also have a blog that's worth reading.

Annie Murphy Paul: Author of the forthcoming book Brilliant: The Science of How We Get Smarter

Becky Allen*: Reader in Economics of Education at Institute of Education. Quant wizard.

Becky Francis: Professor of Education and Social Justice at King's College.

Chris Husbands*: Director of the Institute of Education

Dan Willingham: Cognitive Psychologist and Author of Why Don't Students Like School?

Daisy Christodolou*: Research and Development manager at ARK, Author, super-smart.

David Weston*: Former teacher, Chief Executive of the Teacher Development Trust

Dylan William: Professor, expert in assessment and curriculum

Gifted Phoenix: (Not his real name) Education policy analyst specialising gifted and talented

Graham Birrell: Senior Lecturer in Education at Christchurch Canterbury

Laura McInerney*: Former teacher, blogger, columnist, complete genius if a bit too Fabian.

Loic Menzies*: Researcher, Author, Blogger, Teacher Trainer.

Martin Robinson: Author and teacher trainer

Rob Coe: Professor of Education at Durham

Duncan Spalding: Norfolk Headteacher

John Tomsett*: Headteacher in York

Geoff Barton: Head in Suffolk. Frequent tweeter, occasional blogger, not a big fan of Ofqual.

Liam Collins: Head in East Sussex

Rachel de Souza: CEO of the Inspiration Trust; a forward thinking academy chain in East Anglia

Ros McMullen: Principal of David Young Community Academy in Leeds.

Tom Sherrington*: One of the best blogging heads

Ann Mroz: Editor of the Times Education Supplement

Greg Hurst: Education Editor at The Times

Helen Warrell: Covers education for the Financial Times

Jonn Elledge: Editor of Education Investor Magazine. More left wing than that makes him sound.

Michael Shaw: Director of TESPro

Nick Linford: Editor of FE Week

Reeta Chakrabati: BBC Education Correspondent

Richard Adams: Education Editor at the Guardian

Sanchia Berg: BBC education specialist; currently on Newsnight

Sean Coughlan: BBC online education correspondent

Sian Griffiths: Education Editor at the Sunday Times

Toby Young: Free School Founder, columnist, provocateur.

Warwick Mansell*: Guardian Education Diarist, freelancer, blogger.

William Stewart: Reporter at the Times Education Supplement

Andrew Adonis: Former education Minister and Author

Brett Wigdortz: CEO of Teach First and my boss.

Conor Ryan: Former adviser to David Blunkett and Tony Blair. Now at Sutton Trust.

Dominic Cummings: Former Special Adviser to Michael Gove

Fiona Millar: Columnist and campaigner for comprehensives; former adviser to Cherie Blair.

Gabriel Sahlgren: Research Director at the Centre for Market Reform of Education.

Gerard Kelly: Former Editor of the Times Education Supplement.

Graham Stuart: Chair of the Education Select Committee

Jonathan Clifton: Senior Research Fellow at IPPR, working on education and youth policy.

Jonathan Simons: Head of Education at Policy Exchange. Ex-cabinet office.

Michael Barber: Chief Education Advisor at Pearson. Former Head of the PM’s Delivery Unit.

Pasi Sahlberg: Finnish education expert - author of Finnish Lessons

Robert Hill*: Former adviser to Charles Clarke and Tony Blair. Currently advising Welsh Govt.

Stephen Tall*: Development Director at the Education Endowment Foundation

Tim Leunig: DfE Director of Research

Tom Richmond: Policy Adviser to Nick Boles

Tristram Hunt: Shadow Secretary of State for Education

Alex Quigley*: Subject Leader of English & Assistant Head. One of my favourite bloggers.

Alex Weatherall: Science / Computer Science teacher

Andrew Old*: Anonymous teacher; caustic, brilliant, blogger and Man of Mystery

David Didau*: Teacher, Author and one of the most popular teacher bloggers.

Debra Kidd*: AST for Pedagogy, formerly Senior Lecturer in Education, MMU.

Harry Fletcher-Wood*: History teacher and CPD leader at Greenwich Free School.

Harry Webb*: Ex-pat Brit teaching in Australia. Great, analytic, blogger.

Katie Ashford*: Secondary English teacher

Keven Bartle*: Senior Leader and entertaining blogger

Kristopher Boulton*: Maths teacher at ARK King Solomon Academy

James Theobold: English teacher. Funny.

Jo (readingthebooks)*: Head of English in a London school.

Joe Kirby*: English teacher + prolific blogger

John Blake*: History teacher and Editor of Labour Teachers

Lee Donaghy*: Senior Leader at Parkview school, Birmingham.

Michael Merrick*: Teacher of many subjects and professional contrarian.

Michael Tidd*: Sussex middle school teacher (KS2) and blogger

Micon Metcalfe: Business Manager at Dunraven School. Edu-finance queen.

Red or Green Pen?*: Anonymous Maths teacher and great blogger

Stuart Lock*: Deputy Headteacher

Tessa Matthews*: Pseudonym for a English teacher + super blogger.

Thomas Starkey*: FE English teacher

Tom Bennett*: Teacher, Blogger, Author, ResearchED Founder, Scot.

SchoolDuggery: Queen of Education on twitter; unclassifiable. Must follow.

The list is ordered alphabetically in categories. The * indicates they also have a blog that's worth reading.

Academics and Writers

Annie Murphy Paul: Author of the forthcoming book Brilliant: The Science of How We Get Smarter

Becky Allen*: Reader in Economics of Education at Institute of Education. Quant wizard.

Becky Francis: Professor of Education and Social Justice at King's College.

Chris Husbands*: Director of the Institute of Education

Dan Willingham: Cognitive Psychologist and Author of Why Don't Students Like School?

Daisy Christodolou*: Research and Development manager at ARK, Author, super-smart.

David Weston*: Former teacher, Chief Executive of the Teacher Development Trust

Dylan William: Professor, expert in assessment and curriculum

Gifted Phoenix: (Not his real name) Education policy analyst specialising gifted and talented

Graham Birrell: Senior Lecturer in Education at Christchurch Canterbury

Laura McInerney*: Former teacher, blogger, columnist, complete genius if a bit too Fabian.

Loic Menzies*: Researcher, Author, Blogger, Teacher Trainer.

Martin Robinson: Author and teacher trainer

Rob Coe: Professor of Education at Durham

Headteachers

Duncan Spalding: Norfolk Headteacher

John Tomsett*: Headteacher in York

Geoff Barton: Head in Suffolk. Frequent tweeter, occasional blogger, not a big fan of Ofqual.

Liam Collins: Head in East Sussex

Rachel de Souza: CEO of the Inspiration Trust; a forward thinking academy chain in East Anglia

Ros McMullen: Principal of David Young Community Academy in Leeds.

Tom Sherrington*: One of the best blogging heads

Journalists

Ann Mroz: Editor of the Times Education Supplement

Greg Hurst: Education Editor at The Times

Helen Warrell: Covers education for the Financial Times

Jonn Elledge: Editor of Education Investor Magazine. More left wing than that makes him sound.

Michael Shaw: Director of TESPro

Nick Linford: Editor of FE Week

Reeta Chakrabati: BBC Education Correspondent

Richard Adams: Education Editor at the Guardian

Sanchia Berg: BBC education specialist; currently on Newsnight

Sean Coughlan: BBC online education correspondent

Sian Griffiths: Education Editor at the Sunday Times

Toby Young: Free School Founder, columnist, provocateur.

Warwick Mansell*: Guardian Education Diarist, freelancer, blogger.

William Stewart: Reporter at the Times Education Supplement

Policy and Politics

Andrew Adonis: Former education Minister and Author

Brett Wigdortz: CEO of Teach First and my boss.

Conor Ryan: Former adviser to David Blunkett and Tony Blair. Now at Sutton Trust.

Dominic Cummings: Former Special Adviser to Michael Gove

Fiona Millar: Columnist and campaigner for comprehensives; former adviser to Cherie Blair.

Gabriel Sahlgren: Research Director at the Centre for Market Reform of Education.

Gerard Kelly: Former Editor of the Times Education Supplement.

Graham Stuart: Chair of the Education Select Committee

Jonathan Clifton: Senior Research Fellow at IPPR, working on education and youth policy.

Jonathan Simons: Head of Education at Policy Exchange. Ex-cabinet office.

Michael Barber: Chief Education Advisor at Pearson. Former Head of the PM’s Delivery Unit.

Pasi Sahlberg: Finnish education expert - author of Finnish Lessons

Robert Hill*: Former adviser to Charles Clarke and Tony Blair. Currently advising Welsh Govt.

Stephen Tall*: Development Director at the Education Endowment Foundation

Tim Leunig: DfE Director of Research

Tom Richmond: Policy Adviser to Nick Boles

Tristram Hunt: Shadow Secretary of State for Education

Teachers

Alex Quigley*: Subject Leader of English & Assistant Head. One of my favourite bloggers.

Alex Weatherall: Science / Computer Science teacher

Andrew Old*: Anonymous teacher; caustic, brilliant, blogger and Man of Mystery

David Didau*: Teacher, Author and one of the most popular teacher bloggers.

Debra Kidd*: AST for Pedagogy, formerly Senior Lecturer in Education, MMU.

Harry Fletcher-Wood*: History teacher and CPD leader at Greenwich Free School.

Harry Webb*: Ex-pat Brit teaching in Australia. Great, analytic, blogger.

Katie Ashford*: Secondary English teacher

Keven Bartle*: Senior Leader and entertaining blogger

Kristopher Boulton*: Maths teacher at ARK King Solomon Academy

James Theobold: English teacher. Funny.

Jo (readingthebooks)*: Head of English in a London school.

Joe Kirby*: English teacher + prolific blogger

John Blake*: History teacher and Editor of Labour Teachers

Lee Donaghy*: Senior Leader at Parkview school, Birmingham.

Michael Merrick*: Teacher of many subjects and professional contrarian.

Michael Tidd*: Sussex middle school teacher (KS2) and blogger

Micon Metcalfe: Business Manager at Dunraven School. Edu-finance queen.

Red or Green Pen?*: Anonymous Maths teacher and great blogger

Stuart Lock*: Deputy Headteacher

Tessa Matthews*: Pseudonym for a English teacher + super blogger.

Thomas Starkey*: FE English teacher

Tom Bennett*: Teacher, Blogger, Author, ResearchED Founder, Scot.

And of course...

SchoolDuggery: Queen of Education on twitter; unclassifiable. Must follow.

Saturday, 26 October 2013

Why are London's schools doing so well?

London's secondary schools have been doing better than those in the rest of the country for some time now. They were already ahead in 2003. But the gap has widened over the past ten years to a chasm. Chris Cook - when he was the FT's education correspondent - was the first to analyse this trend in detail. And he realised that the official Government metrics of performance were actually hiding how far ahead London is.

Since then there's been a growing debate amongst policy wonks about why this is happening. But I think most people - even those in the education sector - still don't realise quite how far ahead London is now; especially for poorer children.

In this post I'll give some stats on how big the gap now is. I'll then question whether this is down to policy or socio-economic change. Finally I'll look at whether - if policy has driven some of this change - what that might mean for the rest of the country.

The size of the gap

The gap between London and the rest on the Government's main measure, 5A*-C including English and Maths, is negligible - 59% nationally and 62% in the capital. But that's actually quite surprising given how many more children on free school meals live in London compared to elsewhere (23% vs. 14% at secondary). When we look at just those children on free school meals we start to get a sense of the difference. In London FSM kids get 49% vs. 36% elsewhere. When you dig into LA level data the extremes are startling. Almost two thirds of FSM pupils achieved the 5A*-C benchmark in Westminster last year compared to less than a fifth in Peterborough (the lowest scoring authority).

But because 5A*-C is a simple threshold measure it obscures how much better London schools are doing for the very poorest. The graph below is taken from the recently published Milburn report on social mobility (in fact it's a variant of a graph Chris Cook did a while ago). It shows that children in London do better at GCSE and poorer children do a full grade better - across all their GCSEs - on average. The rich/poor gradient is much less steep meaning that, while London is one of the most economically unequal parts of the country, the education system is producing more equal results.

The next table is from some internal analysis we've done at Teach First. Here we've looked at only those schools that are eligible for Teach First i.e. those where at least half the pupils are in the bottom 30% of the IDACI (Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index).

Nearly all secondary schools in inner London meet this eligibility criteria. In other areas- like the South East just a small percentage do. We've compared the GCSE average points score in eligible schools in different regions (excluding all GCSE "equivalencies" and doubling the value of English and Maths). This shows eligible schools in inner London 100 points ahead of the worst performing regions (the South East and South West) which is equivalent to the difference between 6 D grades and 6 B grades.

It's also important to note that this isn't just a GCSE phenomenon down to - perhaps - better gaming by schools in London. Our initial analysis of the DfE's post-16 destination data shows the pupils from Teach First eligible schools in London have about a 9 in 10 chance of going on to further education - around the national average for all schools - compared to about 8 out of 10 in other parts of the country. Poorer students from London are also much more likely to go to university.

Why is there a gap?

For me the big question is whether this gap has been driven predominantly by policy or by socio-economic changes. If the former then it's good news because. if we can work out which policies and how best to transfer them elsewhere, we can help schools in other parts of the country improve. If the latter then it's good for London but worrying for everywhere else as the gap will continue to grow.There have been a number of policies over the past ten years that have disproportionately benefited London:

- The Labour Government significantly increased school funding across the country but it increased by a higher proportion in London (which was already well funded - albeit with higher salary costs).

- The academy programme started in London and the best sponsors, while not exclusively in London, seem to be concentrated there (e.g. ARK, Harris, Mossbourne, Haberdashers).

- Initiatives like Teach First tend to have started in London even if they were later rolled out to the rest of the country. (If you're in a challenging school in London you won't find it difficult to find a charity nearby offering tutoring or mentoring - in Clacton or Peterborough it's a different story).

- And the one that people talk about most - the London Challenge - a programme launched by Labour as an umbrella for a number of schemes but which was, primarily, about brokering support between stronger and weaker schools. (See this Ofsted report for a good summary).

At the same time the socio-economics of London have changed massively. Essentially London has got a lot richer while much of the rest of the country hasn't. To illustrate here's some startling stats from a BBC article:

"A recent study estimated that the value of London's property had risen by 15% - or £140bn since the financial crisis began. That increase - just the increase - is more than the total value of all residential property in the north east of England. London's top ten boroughs alone are worth more, in real estate terms, than all the property of Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, added together."

And here's a scary infographic from the ONS:

Not only has London got richer. It's got richer in precisely those areas where schools have improved the most. Look at this map discovered by Economist journalist Daniel Knowles. The red areas are those which have gentrified the most over the past ten years; the blue areas have gone "downmarket".

The areas that have seen the biggest change in socio-economic status - Westminster, Southwark, Newham, Tower Hamlets, Hackney - are also the areas which have seen the greatest gains in school performance.

This certainly isn't the whole story behind London's improvement but it's an interesting correlation. The secondary schools in these areas haven't suddenly filled with yuppies' kids, they're nearly all still eligible for Teach First, but many have become more mixed. Moreover, the children in those schools are exposed to very mixed communities, unlike some of the worst performing parts of the country where communities are much more uniform. And those areas have become a lot more attractive to teachers - especially young teachers.

So has policy or economics driven change? Given the lack of in-depth research on the topic all we can is it's a complex mix of factors. The extra money available in London probably helped but it wouldn't have been worth as much without the increased supply of bright young teachers heading towards the capital. Yes lots of charities like Teach First started in London but they did so because that's where recruitment is easiest.

London Challenge is perhaps the most interesting. Many headteachers who were involved will argue it was a hugely valuable experience - though there is little in the way of hard statistical evidence (e.g. comparing improvement in London Challenge schools with other schools in London that weren't part of the programme). But if it did work it was in large part because there was already a supply of excellent headteachers and advisers to provide mentoring and support.

What might it mean for the rest of the country?

The complex relationship between policy and non-policy factors in London mean we have to be very careful about drawing simple conclusions about what might work elsewhere.It would be easy to say - and many have - let's roll out "challenges" in other regions. But they were tried in Manchester and the Black Country and weren't nearly as successful - perhaps because the necessary concentration of existing expertise wasn't there to make it work. And if it isn't there in Manchester it certainly won't be in coastal towns or dispersed rural areas where we have the greatest problems of underperformance.

Likewise there'll be little benefit to changing the funding system to switch funds from London to elsewhere if other schools can't get access to a ready supply of talented new teachers and the types of mentoring/tutoring initiatives that are so prevalent in London.

That doesn't mean regional placed based strategies aren't worth trying - I believe they are - but they need to be bespoke rather than just attempts to recreate London Challenge.

I get the impression that Nick Clegg's unfortunately named Champions' League of Headteachers is the beginning of an attempt to do this; but busing in new heads won't be enough. If regional strategies are going to be tried in the places that need them most there will have to be a concerted effort to create a sense of collective mission. Existing heads and teachers in the areas of focus will have to buy in; successful heads and teachers from other areas (and especially London) will have to recruited to provide support; charities will have to be encouraged to venture out of their urban hubs and, ideally, educational change will be linked to wider community projects and economic regeneration.

Change happened in London but it already had a lot going for it. Making it happen elsewhere will be a lot harder.

Sunday, 20 October 2013

What do the opinion polls tell us about support for free schools?

Opinion polling is a valuable but dangerous tool. Dangerous because superficial analysis can lead to badly misjudging the public mood. And because so few people understand how polls actually work. This weekend I saw people tweeting puzzlement at two polls; one showing Labour with a 3% lead and one with a 11%. But with a margin of error of 4% and very different methodologies between the two polls it's not surprising at all. (The trick to reading voter polls is to look at trends across multiple polls over time).

These two polls happened to both contain questions about free schools after an eventful week for the policy. There isn't really much polling on free schools for such an important policy (politically at least) so it's worth unpicking in some detail.

First ComRes for the Independent on Sunday asked:

Parents, teachers and charities should be encouraged to set up new state schools, even if there are already schools in the local area:

Agree 27%

Disagree 36%

Don’t know 37%

So free schools are unpopular? Not so fast... This is a badly designed, and so misleading, question. The problem is it asks two different things in one question. First should non-state providers be allowed to set up schools and then should they be allowed to do so even if provision already exists. It doesn't tell us how many like the idea of non-state providers but not the "waste" of surplus capacity. And it's confusing- as can be seen by the high number of "don't knows".

Meanwhile Opinium for the Observer asked some much more detailed questions. First they looked at general support for the policy: "Like state / comprehensive schools "free schools" are schools that are funded by the government but, unlike state / comprehensive schools, they are not under the control of the local authority. They can be set up by parents, teachers, charities or businesses and are free to attend."

44% believed that "free schools" are generally a good thing for education in the UK while 22% said they are a bad thing; with a further 22% saying neither good nor bad and 12% don't knows.

Here the focus is on the "free" part not the surplus places and that bit of the policy seems popular; even among Labour voters who were 39/30 in favour (Lib Dems were even more pro - 50/18).

On the specific issue of whether such schools should be allowed to hire unqualified teachers respondents were asked:

"While teachers hired by state / comprehensive schools have to have a PGCE or equivalent teaching qualification, "free schools" are free to hire whoever they choose, as private schools do. The advantage of this is that they can employ people who have more experience of the world outside teaching while the disadvantage is that it may risk children being taught by under qualified teachers."

A resounding 60% were concerned that "free schools" are able to hire teachers who may not have a PGCE or equivalent teaching qualification while 30% are not. Amongst all three parties' voters there were more "concerned" than "not concerned". So that bit of the policy doesn't seem very popular.

But perhaps most interesting Opinium asked about what respondents wanted a future Government to do about free schools. Here responses were divided. 23% wanted the policy to continue as is (this was the most popular for Tory voters).

27% wanted what is - in effect - Labour's current policy- to allow them to continue but only in areas where there aren't enough places and if all teachers are qualified. This was the most popular option for Liberal Democrats - just beating leaving the policy as it is - and the equal most popular amongst Labour voters.

Just 12% wanted to prevent any further free schools from opening while leaving the existing ones alone and 20% thought that all free schools should be taken under local authority control (this was equal most popular with Labour voters).

What does all this tell us? It seems the majority of voters like the idea of non-state providers being allowed to set up their own schools but that they really don't like the idea of unqualified teachers. Most people want the policy to continue in some form but those that do are pretty split between allowing them in areas that already have enough places. So Labour's current policy is probably most in tune with the public (if they could explain it clearly...)

I expect, as we approach the next election, more polling companies will look in detail at this issue so we should be able to see if these hypotheses hold as people learn more about the policy.

Thanks to Daniel Boffey at the Observer for sending me the Opinium numbers. When these appear on the Opinium website I'll add a link.

Friday, 11 October 2013

Thoughts on the OECD survey of adult skills

The first OECD survey of adult skills (PIAAC) was published this week. It's a fascinating - and, at almost 500 pages, immense - report. As England comes close to the bottom of the league tables - especially amongst 16-24 year olds - it has been presented as a condemnation of our education system. And you'd have to be remarkably complacent to read the report and not be concerned about our apparent global weakness in basic skills but it's worth highlighting some things that a superficial reading might miss:

1) The report isn't really telling us anything we didn't already know from PISA - the OECD's existing international comparative test for 15 year olds. It looks worse than PISA because we're at the bottom of the league table rather than somewhere in the middle, and our scores are below average rather than average, but that's a bit misleading. Far fewer countries participated in this survey than in PISA and most of those that did also do better than us in that test.

2) Those countries that did better than us in PIAAC but not PISA (e.g. France, Sweden, Czech/Slovak Republic) all have compulsory literacy and numeracy for those in post-16 education. As do pretty much all the other countries that participated. As a majority of our 16-18 year olds don't study English or Maths it's not really surprising that even countries we're marginally ahead of in PISA do better than us in PIAAC. If we were to increase the numbers of 16-18 year olds doing these subjects (as both the Government and Labour want to do) I'd expect to see us rise up the tables a bit.

3) The questions PIAAC uses (like PISA) are very applied - i.e. are focused on using literacy and numeracy in "everyday" situations. Our education system doesn't focus on applied skills in the way that others do; especially post-16. By contrast the other big international comparative test for 15 year olds, TIMSS, tests whether pupils have mastered the specific knowledge and skills outlined in curriculum content common amongst participating countries. We do much better in TIMSS than PISA so it's fair to assume our post-16 issue is also with applied skills rather than curriculum skills. All of which seems to support mathematician Tim Gowers' proposal for post-16 courses in real-world maths.

4) This difference between applied and curriculum skills may go someway to explaining how it can feel to so many people that our system has improved over the last 15 years despite our PISA results flatlining and our PIAAC results showing our 16-24 year olds doing so badly. We may have improved a lot in things that PISA/PIAAC don't measure; while making little progress in things they do. Another factor may be that the politics/media world tends to focus on London where the system almost certainly has improved while ignoring continued underperformance in other parts of the country.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)