Tuesday, 3 December 2013

Is this plagiarism?

So I noticed some similarities between my earlier blog on today's PISA results and Wednesday morning's Times leader column.

Below I've quoted the leader column followed by the similar line from my blog in italics.

Plagiarism or sloppiness?

"Economies such as Brazil, Indonesia, Mexico and Turkey are starting to educate their populations better too, especially in reading."

"The charts below show the countries that have consistently improved in reading...what stands out is the number of "emerging economies" in this group like Brazil; Indonesia; Mexico and Turkey."

"The same is true of many of the former Warsaw Pact countries such as Estonia, Poland, Russia and Hungary, all of which are improving quickly."

"We can also see big improvements in many of the former USSR/Warsaw Pact countries like Estonia, Poland, Russia and Hungary."

"The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) points out that nations in the Far East do well because they have a cultural fixation with hard work rather than any innate ability."

"The OECD argue that the single biggest reason why the Far East does so well is that they do not have the fixation with innate ability that many Western countries have."

"Many of the most improved nations, such as Estonia, Mexico and Israel, have recently been making their entry criteria to the teaching profession tougher."

"Many of the most improved countries like Estonia, Mexico and Israel have been toughening entry criteria to the profession"

"The countries that do well have, without exception, what the OECD calls “system stability”.

"Most [successful countries] have "system stability"

That last one's a bit of a giveaway - I use the phrase "system stability" but it doesn't appear anywhere in the OECD report...

10 Things You Should Know About PISA

`

1. PISA isn't precise but isn't useless either. No methodology designed to compare countries with completely different cultures and education systems will ever be perfect. The OECD acknowledge that their rankings aren't exact and it makes more sense to look at buckets of countries who have similar scores:

It may be that they're underplaying the statistical issues with the tests (see Professor David Spiegelhalter's concerns here). But that doesn't mean that PISA is worthless. In fact it's far more reliable (along with the other global tests - TIMSS and PIRLS) than any other method of comparison. While we shouldn't rely on the exact rankings we can look at broad trends - especially over time.

2. PISA tests something quite specific. The questions PISA uses are applied - i.e. are focused on using literacy and numeracy in "everyday" situations. Some education systems focus their curriculum more on this type of learning than others. By contrast TIMSS tests whether pupils have mastered specific knowledge and skills which, again, some systems focus on more than others. The UK and US do much better in TIMSS than PISA - and always have.

So with those caveats...

3. The UK is very very average. In Maths and Reading there's no statistically significant difference between the UK and the OECD average. Even on each individual question type (subscales) in Maths the UK is bang on average. Only in Science is the UK slightly above average - as it was last time. There is also no real change from the previous round of PISA. The UK's science score is exactly the same as last time; while Maths and Reading have seen a fractional but not significant improvement. As the graph below shows the UK is one of fairly large group of countries that have seen no meaningful change over the past ten years. All those policies; all those rows and - at least on what PISA measures - no change.

4. The Far East is dominant. Far Eastern countries have always done well in PISA but they are moving away from everyone else. The top seven jurisdictions in Maths are all Far Eastern (though four of the seven are cities or city-states). Shanghai's 15 year olds are now a full three years ahead of the OECD average - and thus the UK - in Maths (40 points translates roughly into one year of learning). Also look, in the table below, at the number of "top performers" in Shanghai compared to the OECD average:

It's worth noting that there are some question marks about Shanghai's performance. For instance they exclude the children of migrant workers. And of course Shanghai is not China. If you plucked London out of the UK it would almost certainly do better than the country average.

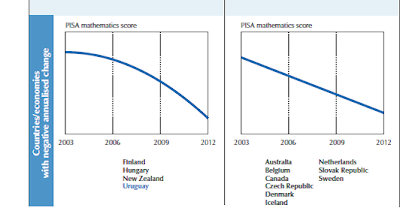

5. Scandinavia is in decline. One of the big stories from this PISA dataset is Finland's significant drop - especially in Maths. They've actually been declining over the past few iterations but the drop this time is much bigger. In fact they're one of only four countries where Maths scores are falling at an accelerating pace (see chart below on the left). But something broader is happening in Scandinavia. If you look at the chart on the right you can see Denmark, Sweden and Iceland have been falling steadily over the past ten years too. Norway has remained static over the same period. Given these countries have fairly different policy environments there may be demographic factors at play here - for instance increasing immigration could be making these countries less socially homogenous.

6. The emerging economies are on the rise. The charts below show the countries that have consistently improved in reading since 2000. While there's a mix of different countries; what stands out is the number of "emerging economies" in this group like Brazil; Indonesia; Mexico and Turkey. These countries are starting from a low base and still do considerably worse than the UK and other developed nations but their rapid improvement is encouraging from the perspective of global prosperity. Often the improvement in these countries is a result of getting more children into school and keeping them their longer. Between 2000 and 2011 the number of children not in school, globally, fell by almost half. We can also see big improvements in many of the former USSR/Warsaw Pact countries like Estonia, Poland, Russia and Hungary. The former two are now among the best performers in Europe.

7. National scores hide huge regional variations. Some countries run the tests in such a way as to allow sub-regions to be given separate scores. The differences are often startling. For instance the Trento region in the north of Italy would be in the top ten globally for Maths if it was a country but pupils in Calabria in the south are around two and half years behind. Likewise in Australia pupils in the Capital Territory (i.e. Canberra) are almost two years ahead of those in the Northern Territory (where many indigenous Australians live). And Flemish Belgium does miles better than French Belgium. In the next PISA we'll be able to see England by region and we can expect to see London and the South-East outperforming other areas. We can already see Wales significantly underperforming the rest of the United Kingdom - the gap's got fractionally larger since last time.

8. There are some policies that many of the "rising" countries seem to share. One of the trickiest things about PISA is making causal links between specific policies and changes in countries' scores. It's very hard to not just cherry-pick examples that support one's existing views. There do seem to be, though, some strong themes around the most successful and most improved countries. One is selection - Germany and Poland are both reducing selection in their systems and have seen improvements and a reduction in the impact of socio-economic status on performance. Singapore is really the only high-performing country to have any selection in their system. A focus on the status of teaching does also seem to be important. This has always been true in the Far East but many of the most improved countries like Estonia, Mexico and Israel have been toughening entry criteria to the profession; raising teacher pay and improving access to professional development. Most successful countries also seem to give a reasonable amount of autonomy to schools. And most have "system stability" - i.e. they have planned reforms backed by much of the system taking place over an extended period of time; rather than constant, uncoordinated, changes.

9. High expectations are absolutely key. The OECD argue that the single biggest reason why the Far East does so well is that they do not have the fixation with innate ability that many Western countries have (yes I'm looking at you Boris). As they put it:

"The PISA 2012 assessment dispels the widespread notion that mathematics achievement is mainly

a product of innate ability rather than hard work. On average across all countries, 32% of 15-year-olds do not reach the baseline Level 2 on the PISA mathematics scale (24% across OECD countries), meaning that those students can perform –at best – routine mathematical procedures following direct instructions. But in Japan and Korea, fewer than 10% of students – and in Shanghai-China, fewer than 4% of students – do not reach this level of proficiency. In these education systems, high expectations for all students are not a mantra but a reality; students who start to fall behind are identified quickly, their problems are promptly and accurately diagnosed, and the appropriate course of action for improvement is quickly taken."

10. There's loads more interesting stuff. The above points are all taken from Volume 1 of the PISA report. There are another five volumes that will need to be trawled for further insights. Volume 2 is particularly important because it looks at the impact of socio-economic status (SES) on performance. Again SES seems to explain an average amount of the UK's variation but in the most successful countries it plays much less of a role.

Here's the link to the full report: bit.ly/PISA2012

1. PISA isn't precise but isn't useless either. No methodology designed to compare countries with completely different cultures and education systems will ever be perfect. The OECD acknowledge that their rankings aren't exact and it makes more sense to look at buckets of countries who have similar scores:

It may be that they're underplaying the statistical issues with the tests (see Professor David Spiegelhalter's concerns here). But that doesn't mean that PISA is worthless. In fact it's far more reliable (along with the other global tests - TIMSS and PIRLS) than any other method of comparison. While we shouldn't rely on the exact rankings we can look at broad trends - especially over time.

2. PISA tests something quite specific. The questions PISA uses are applied - i.e. are focused on using literacy and numeracy in "everyday" situations. Some education systems focus their curriculum more on this type of learning than others. By contrast TIMSS tests whether pupils have mastered specific knowledge and skills which, again, some systems focus on more than others. The UK and US do much better in TIMSS than PISA - and always have.

So with those caveats...

3. The UK is very very average. In Maths and Reading there's no statistically significant difference between the UK and the OECD average. Even on each individual question type (subscales) in Maths the UK is bang on average. Only in Science is the UK slightly above average - as it was last time. There is also no real change from the previous round of PISA. The UK's science score is exactly the same as last time; while Maths and Reading have seen a fractional but not significant improvement. As the graph below shows the UK is one of fairly large group of countries that have seen no meaningful change over the past ten years. All those policies; all those rows and - at least on what PISA measures - no change.

4. The Far East is dominant. Far Eastern countries have always done well in PISA but they are moving away from everyone else. The top seven jurisdictions in Maths are all Far Eastern (though four of the seven are cities or city-states). Shanghai's 15 year olds are now a full three years ahead of the OECD average - and thus the UK - in Maths (40 points translates roughly into one year of learning). Also look, in the table below, at the number of "top performers" in Shanghai compared to the OECD average:

It's worth noting that there are some question marks about Shanghai's performance. For instance they exclude the children of migrant workers. And of course Shanghai is not China. If you plucked London out of the UK it would almost certainly do better than the country average.

5. Scandinavia is in decline. One of the big stories from this PISA dataset is Finland's significant drop - especially in Maths. They've actually been declining over the past few iterations but the drop this time is much bigger. In fact they're one of only four countries where Maths scores are falling at an accelerating pace (see chart below on the left). But something broader is happening in Scandinavia. If you look at the chart on the right you can see Denmark, Sweden and Iceland have been falling steadily over the past ten years too. Norway has remained static over the same period. Given these countries have fairly different policy environments there may be demographic factors at play here - for instance increasing immigration could be making these countries less socially homogenous.

6. The emerging economies are on the rise. The charts below show the countries that have consistently improved in reading since 2000. While there's a mix of different countries; what stands out is the number of "emerging economies" in this group like Brazil; Indonesia; Mexico and Turkey. These countries are starting from a low base and still do considerably worse than the UK and other developed nations but their rapid improvement is encouraging from the perspective of global prosperity. Often the improvement in these countries is a result of getting more children into school and keeping them their longer. Between 2000 and 2011 the number of children not in school, globally, fell by almost half. We can also see big improvements in many of the former USSR/Warsaw Pact countries like Estonia, Poland, Russia and Hungary. The former two are now among the best performers in Europe.

7. National scores hide huge regional variations. Some countries run the tests in such a way as to allow sub-regions to be given separate scores. The differences are often startling. For instance the Trento region in the north of Italy would be in the top ten globally for Maths if it was a country but pupils in Calabria in the south are around two and half years behind. Likewise in Australia pupils in the Capital Territory (i.e. Canberra) are almost two years ahead of those in the Northern Territory (where many indigenous Australians live). And Flemish Belgium does miles better than French Belgium. In the next PISA we'll be able to see England by region and we can expect to see London and the South-East outperforming other areas. We can already see Wales significantly underperforming the rest of the United Kingdom - the gap's got fractionally larger since last time.

8. There are some policies that many of the "rising" countries seem to share. One of the trickiest things about PISA is making causal links between specific policies and changes in countries' scores. It's very hard to not just cherry-pick examples that support one's existing views. There do seem to be, though, some strong themes around the most successful and most improved countries. One is selection - Germany and Poland are both reducing selection in their systems and have seen improvements and a reduction in the impact of socio-economic status on performance. Singapore is really the only high-performing country to have any selection in their system. A focus on the status of teaching does also seem to be important. This has always been true in the Far East but many of the most improved countries like Estonia, Mexico and Israel have been toughening entry criteria to the profession; raising teacher pay and improving access to professional development. Most successful countries also seem to give a reasonable amount of autonomy to schools. And most have "system stability" - i.e. they have planned reforms backed by much of the system taking place over an extended period of time; rather than constant, uncoordinated, changes.

9. High expectations are absolutely key. The OECD argue that the single biggest reason why the Far East does so well is that they do not have the fixation with innate ability that many Western countries have (yes I'm looking at you Boris). As they put it:

"The PISA 2012 assessment dispels the widespread notion that mathematics achievement is mainly

a product of innate ability rather than hard work. On average across all countries, 32% of 15-year-olds do not reach the baseline Level 2 on the PISA mathematics scale (24% across OECD countries), meaning that those students can perform –at best – routine mathematical procedures following direct instructions. But in Japan and Korea, fewer than 10% of students – and in Shanghai-China, fewer than 4% of students – do not reach this level of proficiency. In these education systems, high expectations for all students are not a mantra but a reality; students who start to fall behind are identified quickly, their problems are promptly and accurately diagnosed, and the appropriate course of action for improvement is quickly taken."

10. There's loads more interesting stuff. The above points are all taken from Volume 1 of the PISA report. There are another five volumes that will need to be trawled for further insights. Volume 2 is particularly important because it looks at the impact of socio-economic status (SES) on performance. Again SES seems to explain an average amount of the UK's variation but in the most successful countries it plays much less of a role.

Here's the link to the full report: bit.ly/PISA2012

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)